When the famous explorer of tragic death Roald Amundsen, first to reach the South Pole during his epic Antarctic expedition in 1912, headed for the opposite end of the globe (90º north) sailing on the Italian zeppelin Norge, he made a last stopover in Vadso, where the mast is still on foot that serviced the airship. Amundsen, one of those real adventurers that existed before the era of credit cards and mobile phones put an end to such job, disappeared forever in the Barents Sea two years after later, ironically during a rescue mission; and so he found his grave in the snowy and icy latitudes he had so much loved.

Today I’m visiting that island of drinking water (such is the meaning of Vadsoya) and thus pay a small tribute to those explorers who did not hesitate in sacrificing their lives–in exchange, yes, for glory, but mostly following their passions.

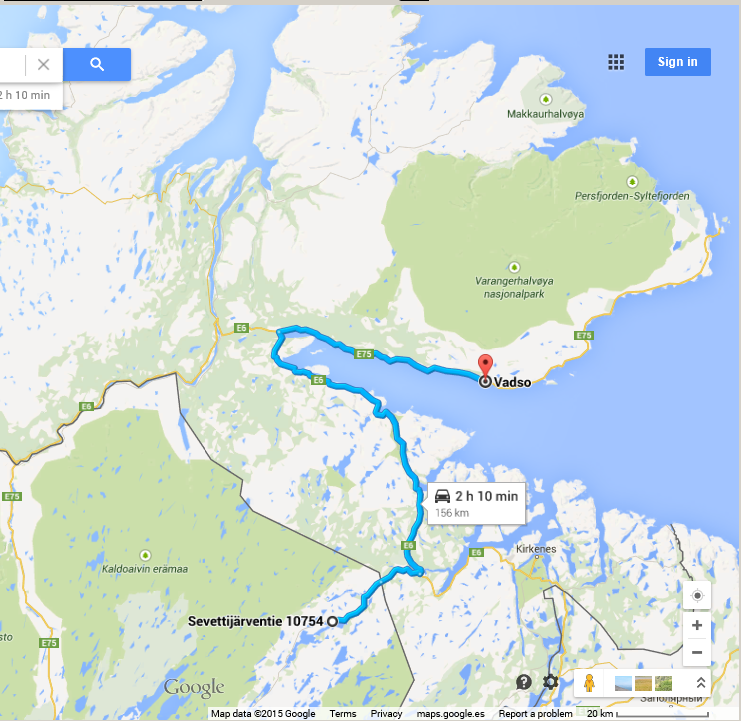

It is a cool and cloudy morning when I put my few belongings into Rosaura’s cases and, heading for the Norwegian border, leave behind the cozy reindeer farm Toini Sanila. The weather change has settled, and I’ll be riding for the next few weeks on the full lined jacket, which now leaves some emptiness in the topcase. Before crossing the border I make a stop at Näätämö for refueling and drinking a tea; actually nothing else can be done here: Näätämö is just that, a motel and a gas station. By the way, I should have refueled yesterday in Inari, because here, Norway being round the corner, fuel is twelve cents more expensive.

This is my farewell to Finland for a few weeks, until God knows when, as I have no idea where shall my steps take me, or perhaps Rosaura’s–as sometimes I believe it’s she who steers me. There are five or six people in the kahvila, either lunching a hot dog or sipping a coffee. I order tea with a bun, then sit at a table and warm up my hands with the glass. It’s a well heated cafeteria. In this land it’s not unexceptional, I guess, to turn the heating on by beginning of August. Here’s a toast to the health of Lapland. From now on it will be Norway, the world’s most expensive country. I have some qualms about the prices, knowing not how long I’ll be able to stay before my budget cracks. But anyway, it won’t be a big issue because Sweden is never farther than fifty kilometers. Now it’s time to keep going.

Right on the border there’s no other sign than a small plate saying Norge, without the yellow starred ring because I’ve just left the EU, though this is still Schengen territory for free transit of people, goods and money. Only a few kilometres farther I make the first stop in this country, by the bridge over Njávdánjohka, which makes a cute waterfall before flowing into Munkefjord. There are a few cars in the parking lot with Finnish or Norwegian plates, and people are taking photographs. From here on and along the next 130 km the landscape will change drastically. Woods will lose their prevalence and yield to a desolate tundra.

Roads are also going to change: more winding, narrow and worn out. It is said that Norwegians are stingy because, wealthy as they are, they don’t spend a dime in repairing their roads; but I don’t believe so; rather I think they’re more like Canadians: having thousands of kilometres of roads under extreme winter conditions, they can’t keep up with repairs. In fact, I’ll come across many more stretches under construction in Norway than in Finland.

Forty kilometres further, for the first time in my life I catch sight of the Arctic ocean in its full beauty. And I mean in its full beauty because technically I had seen it before, when I went by Akureyri during my epic trip around the Hring Végur, the Icelandic ring road, though in that time I barely managed to see the dark stripe of Eyjafjord flanked by steep snowy hillsides. That’s why I now gaze at the Arctic as something new to me, a shallow and calm ocean with turquoise hues I had not imagined, telling of an abounding marine life.

Being the tides so strong in this part of the globe, and the coastline incline so soft, large strips of seabed get exposed at the ebb, as wide as half a mile in some places, and on those huge marshes the kingdoms of sea and land meet, bustling in rich and diverse wildlife.

As I am enjoying my first observation of the Arctic, from a viewpoint unsheltered from the wind, a man addresses me who is around there, apparently doing the same. He’s a nice Norwegian who welcomes me to his country and says he lives not far from North Cape, only in the nearer peninsula to the east, Nordkinn, which rivals with her sister Knivskjellodden the record of enclosing the northernmost tip of the continent, as he kindly explains on a map. Despite Nordkapp being the European cape closest to the Pole, it happens to be on Mageroya island, i.e., separated from the mainland by a stripe of sea; therefore, strictly speaking, Kinnarodden is the northernmost cape in the continent (this is the key). But all of this is just a trivial local rivalry, because the difference between both capes is less than two minutes’ latitude, i.e. two nautical miles.

He has a warm look about him, this blue-eyed Norwegian, but there’s something more to his look than just affection; something I haven’t yet fingered when we shake hands at goodbye. I’d have liked to talk a bit longer with him, as I not too often have the chance of enjoying a fine chap, but it’s cold here and there’s not a shelter.

A few minutes later I stop again, and as I’m taking some shots here arrives the guy in his car, whom I had left behind, and parks by the motorcycle. Probably he also misses a longer chat, I guess. After contemplating the view for a few minutes, I ask him about sightseeing tips in Finnmark county (this part of Norway). As the chill wind doesn’t gives us a break, we get into the car for him to tell me. He unfolds the map and explains to me, here the peninsulas, here the roads, this one going up through Nordkinn towards Gamvik is as beautiful as the one to Nordkapp, yet much less touristic. Precisely along that road he has a summer cottage–he adds, somehow implying an invitation. For the moment I’m heading Vadso–I tell him–but if I decide on taking that road I wouldn’t mind to drop by for a coffee. Then he looks at me again from behind his blue eyes, which sparkled with a fleeting joy; and before he can speak another word, as I’m gazing his glance, I get a glimpse of what throbs beyond his warmth: it’s something intrusive, almost invasive; and I suddenly understand…

These days back–he tells me, but it was already unnecessary–I’ve had my boyfriend at home, whom I’ve just seen to the Kirkennes aerodrome; so I wouldn’t mind to spend a nice while with a foreigner if he pays me a visit. He stares at me to check how much I’ve been impressed by his words; and this time I find his gaze almost aggressive. I reply I’m not in that business, but if it’s just for a coffee I keep my offer. And so the subject is settled because then he makes some excuse, the track to his cottage is a very rough one, barely passable for a four wheeler, leave aside a bike like mine…

When I step off the car we shake hands again and wish him good luck while inwardly cursing mine: why I don’t like men? Only queers come along so near me.

At the end of the fiord that I’m skirting for the past forty kilometres there is Varangerbotn, a tiny settlement with a bunch of houses around a gas station, a hotel and two restaurants. Despite being so small, there’s some life in this place, being the junction where the main route joins the road coming from Vadso and beyond, servicing 150 km of shipping villages. I make a short stopover here for putting something in my stomach. Jagerstua Vertshus is a quite inviting restaurant and souvenir shop where, among the half dozen spread out customers sitting at the tables, I’m able to spot two or three travelers, out of that subtle but unmistakable pose we so well make out, that special demeanour like if saying: here I am, an inured and experienced fellow getting ready for new, unheard of adventures.

And this is my first encounter with Norwegian life level: a teabag plus a slice of cake, fourteen euros: about four times more expensive than Spain and ten times in Poland. I was made aware I’d come across disproportionate prices, but such a rip-off beats my forecasts. On the other hand, despite Norway having oil, gasoline is also considerably pricier than anywhere else: 2 €/l. But this is how it goes and I’d rather get used to it unless I want to spoil my stay.

Fifty kilometres east of the junction I finally reach Vadso, my goal for today. It’s a pleasant and quiet town of about six thousand inhabitants, offering several lodgings, two gas stations and a small variety of restaurants. Though most of the town lays along three or four streets, parallel to the peninsula’s coastline and lined with wooden houses, the original fishing settlement from XVIth century was on the small island right across the bridge: Vadsoya. When later on barter trade started with Russia, the village developed and moved to the mainland. For centuries, it was partly populated by Russians and Finn, and even today Finnish is spoken in several households.

Scandic Vadso is the main hotel, right “downtown”, but as we’re talking about three figures, the receptionist very kindly suggests me to try Lailas Gjestehus, right across the bridge. But before that I try my luck in a couple of guest houses I’ve seen around here, the kind of place that have a hand written sign advertising rom, rooms, which I presume sensibly less expensive. But the first one is under refurbising and I don’t want to be woken up by early morning noises; and as to the second, the landlady doesn’t take credit cards and I don’t have Crowns yet. So this helps me make up my mind for trying Lailas, over in Vadsoya, and see how I like it; if it’s below one hundred I’ll take it.

Lailas Gjesthus is a pleasant family hotel, inviting and well equipped, placed on an unbeatable location in the islet: on its northern shore, surrounded by nature and with great views to Vadso and the fiord. (By the way, a fiord, so fine and select as it sounds just because it’s a Norwegian thing, is nothing but a sea inlet.) The landlady welcomes me behind the desk with a nice smile. Yes, there are vacancies; no, we haven’t single rooms, but as you travel alone let’s make it eighty for a double, is that ok? Or if it’s still too expensive for you, as I know Norwegian prices are really high for foreigners, I can call to a cheaper place downtown and book a room on your behalf; as you please. Wow! That is extremely kind of her, and reveals a praiseworthy lack of greediness; but the fact is, I like this hotel and the room is neat with a lovely view, so we have a deal.

After a good hot shower I go exploring Vadso. First thing I do is withdraw cash; second, getting myself a Norwegian SIM, which is straightforward and easy. Then I look for something to eat, but it turns out there’s not a single restaurant with national food: I find two pizzerias, a Turkish, an Indian, a burger and a hot-dog stand, but nowhere to try some local speciality. Someone explains to me: we Norwegians go out for eating something different than home made food, so we prefer foreign cuisine. What about the tourists?–I ask. Well, that’s the problem: tourists would like to try something typical from here, but no Norwegian in town seems to be interested in starting a national restaurant.

And there is another thing, probably related with the previous one, that strongly calls my attention: the abundance of immigrants from other races. Blacks, Moors, Indians, Turkish, Thais, yellows… I wasn’t expecting this in such a cold country and in so small and remote a town. I had thought–my ignorance, of course–Norway would be almost free from poor countries’ immigrants because, not belonging to the EU, it doesn’t have to comply with our charitable and compassionate social policies. Now, thinking it twice, I realize it just makes sense: Norwegians are so rich, they don’t even take jobs for the poorly qualified; and this way there’s an empty niche ready to be filled by immigrants who’ll work as anything and open pizza places or kebabs so the others can go for dinner something different than home made salmon. This way everybody’s happy.

I leave for dessert a visit to the mast where the airship Norge in the Amundsen expedition was docked in 1926 before crossing the North Pole: it’s still standing upon the wildlife sanctuary–and anthropological reserve–that takes up the whole eastern half of Vadsoya islet. Right there, at one of its three pole’s foot, there’s a conmemorative plate reminding that expedition and the airship’s crew. Those were a different breed of explorers. I don’t say there wouldn’t exist any longer another like them, but is there any unexplored corner left in the planet?

Epilog. Strolling through this small ecological reserve and bird observatory I run into an open wooden shelter in quite good shape, for the visitors use but not abuse. And what do I find? Some of my fellow countrymen have been here leaving a footprint to the shame of Spain: sharcoaled scripts pro and against football teams. I just wonder, what do Norwegians care about the provincial quarrels in one of the most African countries in Europe?