The idea that my head had more or less been giving shape during the previous days was to reach Italy through the Alps trying to avoid when possible the busy Mediterranea seashore; actually, trying to cross when possible the less populated regions; i.e., the inland Roussillon (or Languedoc) from end to end; and this took me two days.

This French region hosts a grid of by-roads that communicate many villages no farther from one another than, average, perhaps five kilometres, despite which -judging by the long stretches of wild country I crossed- it must be one of the areas less densely populated in this country where, today, there is exactly 2.5 acres of land per person.

And it’s a region of a familiar nature, as it reminds me a lot, in geology and flora, my own homeland. Towns and villages are, however, quite different from those of mine, having here an almost pure medieval look that seems to have remained unchanged since five centuries ago. Their inhabitants are apparently not in a hurry for refurbishing or updating their old houses, for replacing the old doors and windows, for renovating the furniture, etc, despite not lacking purchasing power; and in this I see a people that love their past and don’t disown it; a country that loves rural life and is not ashamed of it. Such, at least, is my interpretation when comparing the French countryside with the town-planning harakiris that the Spanish villages are inflicting to themselves for the past four decades.

By the way, the county was radiant, full of large patches of a bush with flowers deep yellow, giving the dark green landscape a touch of joy. Particularly a zone of Languedoc called Pays Cathare.

Thus, in my route across the Roussillon, from Rennes-les-Bains to Vaison-la-Romaine, I came across places like Villerouge-Termenès, whose XIIth century castle, of a military architecture, massive and imposing, was erected as a symbol of the ecclesiastical power, property of the archbishopric of Narbonne until the French Revolution, after which it was sold as national property to a few families, who owned it until very recently.

Or places like Olargues, a village so genuinely medieval -and somewhat labyrinthine- that I wouldn’t be able to represent it in three or four pictures; a full report would be necessary for conveying the images captured by my retina and the impression recorded in my memory. So, I won’t even try. Suffice to put here a panoramic view of the village, its unique and svelte roman bridge, called the Devil’s, and the standing tower of its ruined castle.

And indeed it has, despite its simple elegance, a devilish look this bridge. It’s oftentimes difficult to tell why something reminds us of this or that, but in this case the nickname is quite suitable, though go figure where did it come from; perhaps from a local legend having nothing to do with the bridge’s appearance. Maybe this other picture is more telling:

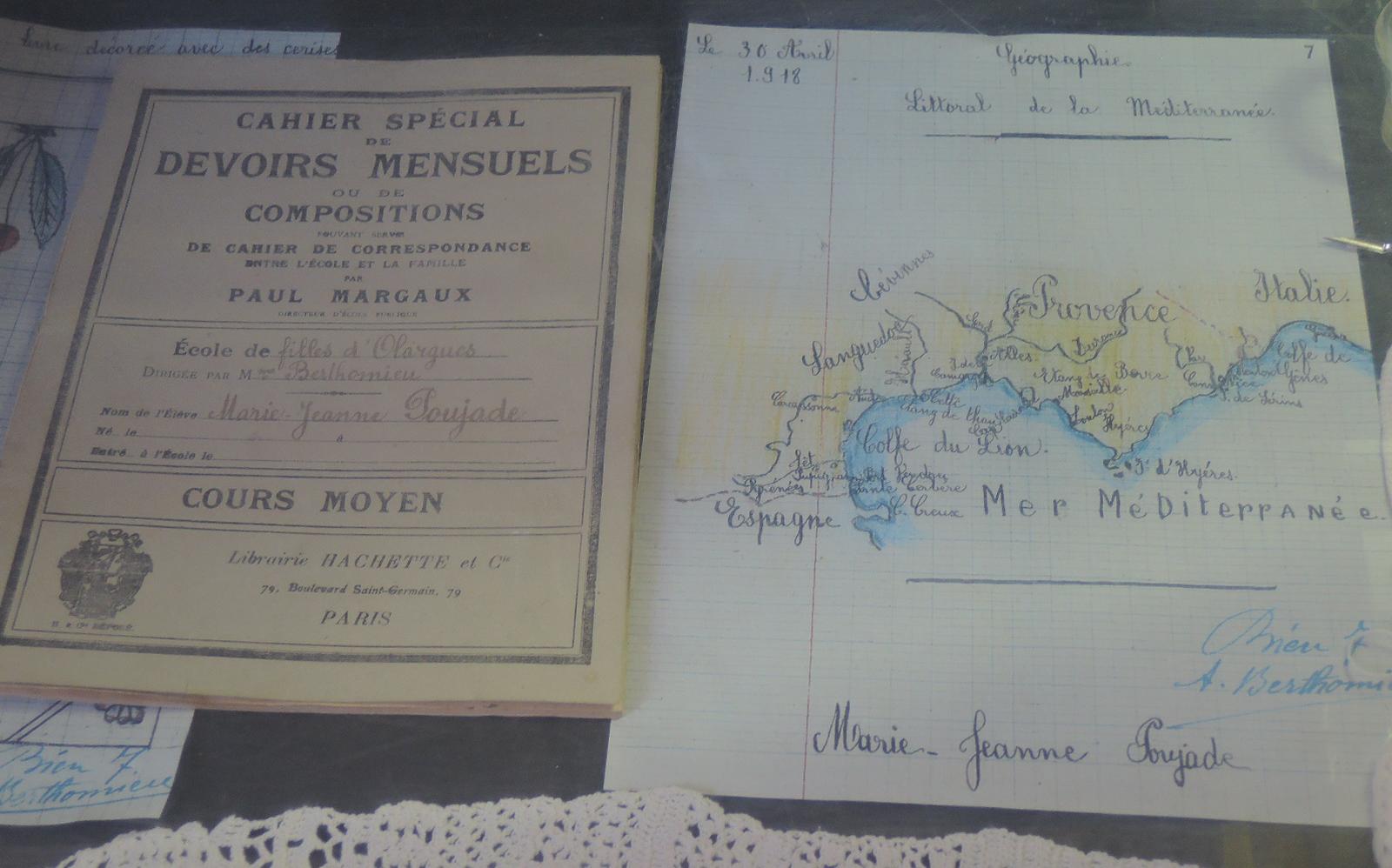

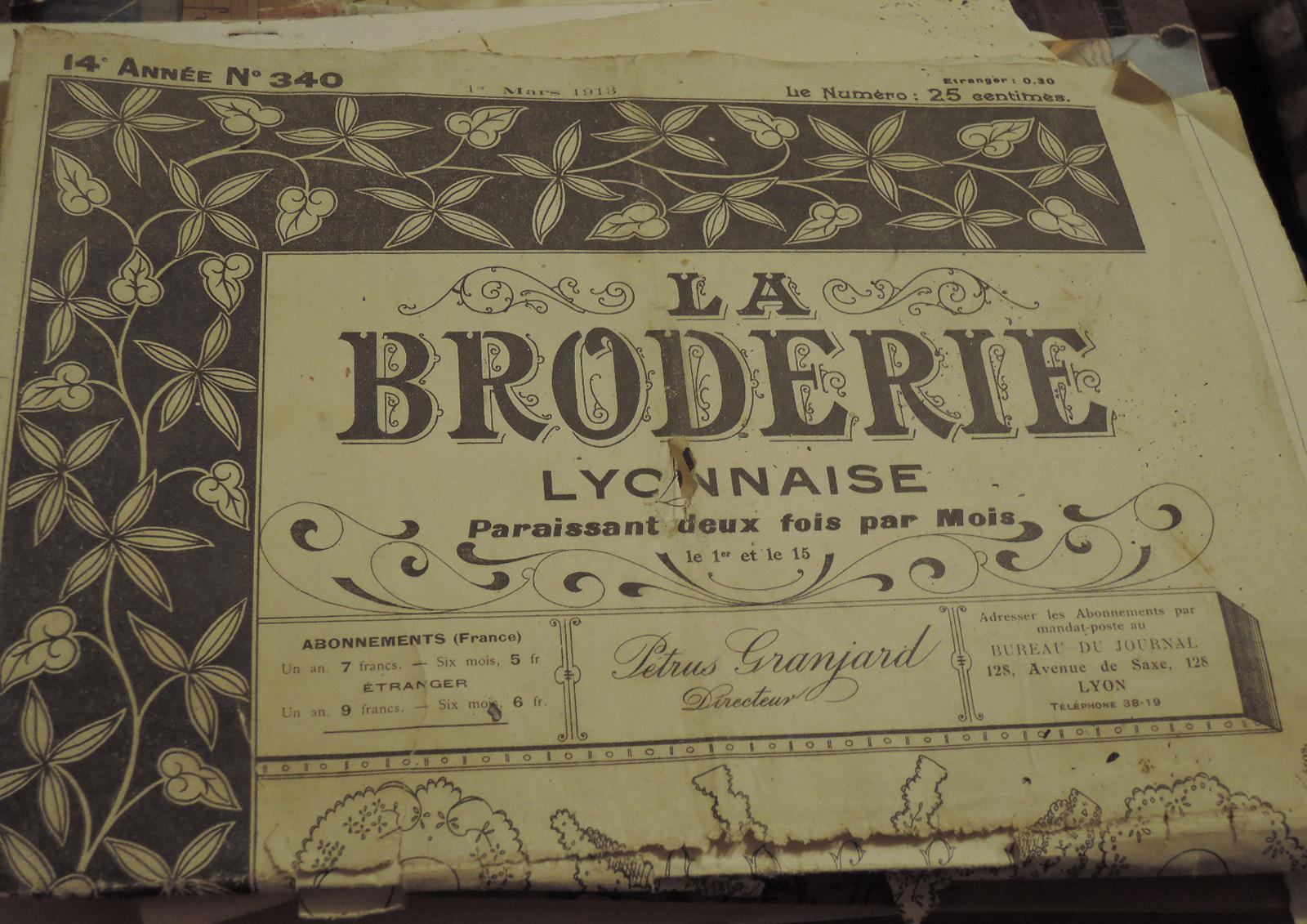

There was also in Olargues a small museum in a huge house from the Middle Ages, of a bizarre and rambling architecture. The museum was dedicated to the popular arts and traditions, for honouring the memories of the deceased, and a few objects called my attention: an exercise book from a girl called Marie-Jeanne Poujade and an old newspaper from Lyon, both dated 1918, soon to finish the World War I.

I don’t know why I paid special attention to those items; maybe because they reminded me of other similar existing in my grandparent’s house, exercise books or papers from the same time, almost one century ago; even not so different from the ones that were still printed when I was a child.

By the way, there was also a kind of diabolical feeling to that mansion, something sinister about it, having two entrances from two different alleys at different levels on the village, with a narrow inner yard surrounded by very high walls, like a square well, and full of corners, massive doors, small windows and vaulted ceilings. Not that any of these elements belongs by its own right to the Kingdom of Darkness, but, had the house been called the Devil’s -after the bridge-, nobody would have thought it strange.

More yet: only by changing a bit one’s approach, I’m sure that, on a grey and stormy winter evening, the whole village of Olargue with its narrrow and twisted streets, its steep slopes and that pointed tower on top of the hill, would take on a fiendish appearance.

But not on this day of deep blue skies; and it was early in the evening when I ended up in a room at a nice hotel in Lodève, a small town full of moors, which didn’t impress me except perhaps for its tree-covered riverside. Besides, I was tired of sightseeing and village-strolling, so my neurons weren’t very receptive; therefore, after one hour of exploring Lodève and taking a couple of pictures, I lied on one of the hotel’s deck chair on its luminous terrace for reading a while before going for dinner, outdoors, at the small garden of a nearby restaurant. Quite a good choice, by the way: it’s been the first time in my experience that the French cuisine matched its international fame.