Three days in Bialystok bring me new acquaintances (like Maka, the young Georgian volunteer, or Grzegorz, the bat researcher) and an unexpected meeting with homeopathy. It’s a farm in the countryside, ten minutes by motorbike from Tykocin, where Beata, a maseuse I had met years ago in Warsaw, lives and works these days. For the past few weeks my shoulder muscles need some fixing, and one of her Hawaian massages can do the magic.

It’s the typical hippy-commune environment every veteran traveller has known at least once: connection with nature, horse riding, spirituality, homeopathy, lots of love for animals and vegetarian food. Among other people, there is a Florida-based Polish lady here, spending her holidays, who claims to be a homeo-therapist; you know the type: body energy and all that prattle, supposedly efective for fixing all kinds of problems, including–or mabybe specially–anxiety and insomnia. Just what I’d need. So, despite my skepticism, the good references I get from Beata help me leave my reticence aside and try a session, since the planets seem aligned. How much?, I ask with caution. Two hundred USD. Wow! An astronomical fee for an astrological medicine; no, thanks. But she makes it easier: since she’s here on holidays and not in labour mode, I’ll tell a price; whatever I feel comfortable with. Since a real massage with Beata costs twenty euros, I can’t pay much more for the alternative. Twenty five? Deal.

The session begins, outdoors, under the trees and among the birds’ tweets. I lay on the table and she puts her fingertips on my head, gengly pressing the mystic energy nodes. She keeps this contact, static, for ten or so minutes, then changes to different spots; a few times like this, now on the head, now on the feet. One hour later the session is over. That’s it. When I stand up, she says my face has changed, my expression is brighter, shinier; look at yourself in the mirror and check. I obey, feeling exactly the same as before, and I check that, indeed, I look exactly the same.

Besides–she explains–, very likely you’ll now feel like eating something sweet, which is normal because we’ve released lots of energy and burnt many carbo-hydrates, that now need being replaced. So, if you want to, go for some sweet; and don’t forget to drink lots of water; minimum two litres. (These North Americans are obsessed with water: the bottled water lobby must sure have an extremely efficient advertising system.)

Needless to say I’m not thirsty nor feel like a cookie; rather I’d like to ask her if the therapists her kind are a bunch of frauds or if, on the contrary, they’re conviced about the healing effects of their practices. Though, actually, what amazes me most of all is: people’s credulity. Once you know how it works, how’s it possible you can believe you’ll get any better by just being touched with the tip of a finger? That’s like believing in miracles. Unless we are, indeed, dealing with the miracle of suggestion; but that’s quite a different thing. If so, maybe in the bottom of myself I envy that credulousness, which could make my life, oh!, so much easier.

For the rest, this farm is quite nice; a bucolic and pastoral environment surrounded by trees and prairies, spotted with cows and horses. I’ve barely ridden twenty kilometres today, but I’m going to stay here for the night and use my evening for a walk to Tykocin, revisiting the village and have dinner there. I keep after the track of my old romance.

Tykocin. I remember this large oblong esplanade with the church at one end; these cobbled streets and this old sinagogue… (Ah, Joanna!) To one side of the square there is a small restaurant serving home made food, run by a lady and her daughter, a rosy peasant of pretty blue eyes. They don’t sell alcohol, but I can buy the beer–I’m instructed–in the shop next door and drink it here. The lady cooks for me a tasteful fish dish, and I get charlotka for dessert. As I enjoy my dinner facing the solitary esplanade, the sun slowly goes down and puts golden tinges on the church’s portico.

When paying the bill I leave a few extra cents, but the lady, dropping all her kindness, in a forbearing tone says: “well, ok”, as if forgiving me. She was expecting a tip –I guess– and, not getting it, lets me know her delusion. A bad habit this, for which I blame the tourists who spoil the commerce.

There’s a long walk to the farm, and upon returning I find the hosts holding a little party with some new guests, right below my room’s window. It’s hard to find some peace even in the middle of nowhere.

Despite the guru’s prognosis, her therapy doesn’t help me in the least to get to sleep, nor have a good rest. In the morrow, I load my things on Rosaura and, beofre departing, I hold a brief conversation with Beata, who rationalizes the failure thus: “people like you can’t be helped, because you don’t allow anyone to get inside yourself”. So: the patient is to blame. Funny; clever response to failure typical from astrologers and necromancers of body energy: if you react positively to homeopathy, they get reinforced; if you don’t, then you’re hermetic and it’s your fault. Their “truth” always prevails.

There is a long and quite labyrinthic set of local tracks leading from the farm to the road, generally firmed down and easy to ride on; but some of the stretches are too sandy, almost impassable on a motorcycle; a real jam. On those stretches, twice I lose the balance, in the verge of having a fall; and if I don’t take a tumble it’s not thanks to my skills, but by sheer chance. As there’s no way back, I have to go ahead maximizing precautions, until I finally come to the asphalt; though such a rough and wrinkled one, that I’d say I’m riding a pneumatic driller. A while afterwards I run into a better road, which in turn, farther on, ends in a regional one in good shape. Finally!

Luckily, it’s a sunny and cool day, very pleasant for riding. My sun glasses polarize the autumn colours of the countryside endowing them with a liveliness that enlightens the soul.

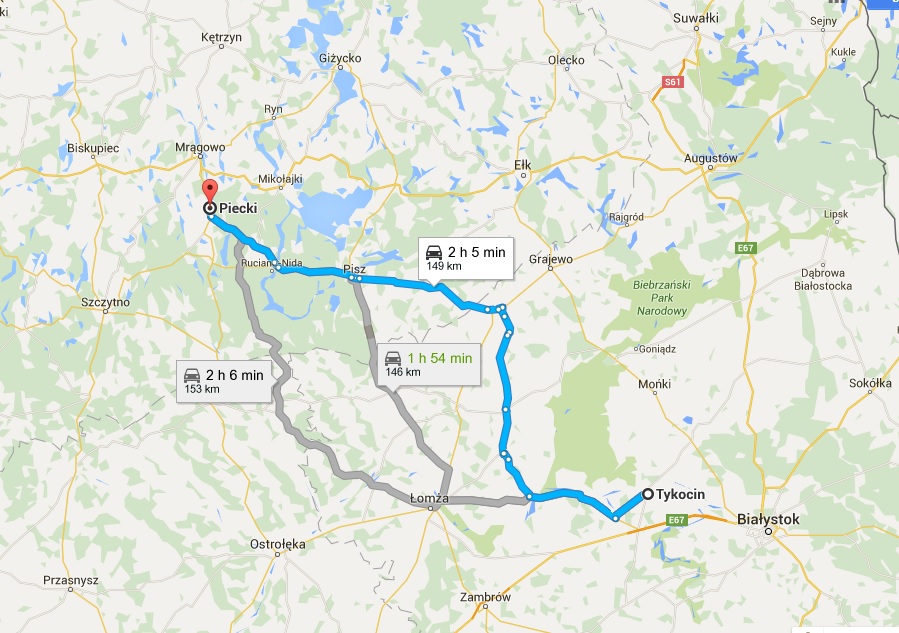

Almost two hours later I arrive to Pisz, where I make a stopover for luch at a typical road obersza; nothing special, but for one euro I’m served a zupa pomidorowa that livens up my stomach. The waiter is a dry fellow, as typical Polish as the soup and the restaurant itself. My leg is aching, probably hurt when I made a fuss to not hit the ground, back on the sand.

An hour later and a few tens of kilometres to the west, in a place called Piecki I find by chance a nice karczma, quiet and very cheap: 50 zl the room; so I don’t think it twice. I was planning to get a bit further today, but I won’t find a better place than this for the night and it’s a perfect afternoon for a long stroll. No worth wasting on the road the two last hours of sunshine.

The village has a cake-shop whose front, facing west, gets bathed in light. There are a few pedestal tables on the boardwalk, and I sit at one of them, tired after my walk, for enjoying a slice of cake on a tea while, closing my eyes, I get warmed up at the late-afternoon sunrays.

And Piecki also has a tiny cemetery with barely half a dozen tombs under the fallen leaves, at the autumn shade of the trees, which remind me of the Spanish poet’s words: Oh, God!, how lonely, how sad are left the dead!

previous chapter | next chapter

Pablo, I just love your rational and down-to-earth approach to the so called “alternative” stuff 🙂

Take care and hopefully see You soon!

Artu