The maelstrom! Could a more dreadful situation have sounded in our ears! We were then upon the dangerous coast of Norway [where], at the tide, the pent-up waters between the islands of Ferroe and Loffoden rush with irresistible violence, forming a whirlpool from which no vessel ever escapes. There, not only vessels, but whales are sacrificed, as well as white bears from the polar regions.

Thus, in his 1870 classic Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, did Jules Verne describe the terrors of the vast maelstrom whirlpool charted by chroniclers since at least the 16th century; but it wasn’t until after Edgard Allan Poe published his bloodcurling tale A descent into the Maelstrom that this word became popular.

It is known today that neither Norway’s maelstrom nor any other oceanic eddy ever creates a whirling funnel of the kind imagined by Verne, Poe, Melville and many earlier writers, but although the menace of such phenomenon was greatly exaggerated, the Moskstraumen –as it is called in Norwegian– is real. Over many centuries it has claimed countless lives among the hapless mariners who ventured into it at dangerous times in the tidal cycle. In any case, 19th-century writers like Poe based their factual errors on old accounts handed down from the Vikings and their kin.

And, however it be, the literary depictions have been powerful and strong enough to make me travel five thousand miles for checking what’s it all about.

The word maelstrom — a synonym in English for a tumult, literal or figurative — is believed to be derived from the Dutch word malen, to grind. An ancient legend has it that a pair of magical millstones were once dropped into the sea off the coast of Norway and that their eternal grinding of sea salt produces the lethal eddies of the maelstrom. But the old Norse people had another name: they called it the havsvelg, which means ‘hole in the ocean’, because they thought it was a bottomless opening into which the water flowed.

Now, after so much anticipation, I’m finally in Saltstraumen for witnessing with my own eyes the famous vortex. August 24th 2014, a windy, sunny and beautiful day. From up the bridge there is a superb view over the strait and the arrow-point shaped stream of the tidal flow rushing into the fjord. The whirilpools (locally called cauldrons) originate on the edges of that arrow. Unfortunately, they’re nowhere near my expectations. Not taht I thought I’d see a fabulous eddy ten metres wide, but certainly not this either. Actually, and but for the fact of knowing that this stream is created by the tide, it is no different than a flowing river of average might.

The treacherous currents in and near the maelstrom are driven by tidal differences in the level of the open sea west of the Lofoten archipelago and that of relatively sheltered water between the islands and the mainland. As the high water streams through coastal fjords and a labyrinth of small islands, it is broken up into many currents, some of which form strong eddies. In the Saltstraumen strait, 150 m wide, 400 millon cubic metres of water flow in about six hours, balancing high and lowtide between the two fjord basins.

So much for the theory. But then again, after a long while watching, this is not getting any better.

In Melville’s novel Moby Dick, the fanatical Captain Achab explains to his crew that the purpose of their voyage is to chase the malevolent white whale that severed the captain’s leg. Aye, aye, said Achab, and I’ll chase him around Good Hope, and round the Horn, and round the Norway Maelstrom, and round perdition’s flames before I give him up.

* * *

And that was it! Curious, but rather disappointing. Now — Saltstraumen being my last aim in Norway — it’s time to leave this country of unbelievable and endless landscapes and return to ‘normal’ Europe. Next mission: get to Sweden — whose border is never too far– aiming for the mountain pass via Junkerdal. Am I willing to go? I’m not quite sure: on one hand I was feeling like a change (and leaving behind the crazy Norwegian prices), but on the other, I’m sad to get away from this fascinating and unequalled land.

Heading southeast from Saltstraumen, the road climbs steadily and we gain considerable altitude in a short distance: only 40 km from the overgrown and relatively populated coast lands to a mountainous region scarcely inhabited and a landscape of sparse woods, small trees and steep grasslandss. It’s quite cold here, and the sky is overcast. I stop to zip in the lining to my jacket, then carry on. Suddenly, behind a corner, a flock of goats blocking the road. As I make my way through them I realize that this is a quite more rural country than we normally imagine when thinking of it. Our minds, I’m afraid, are overloaded with clichés.

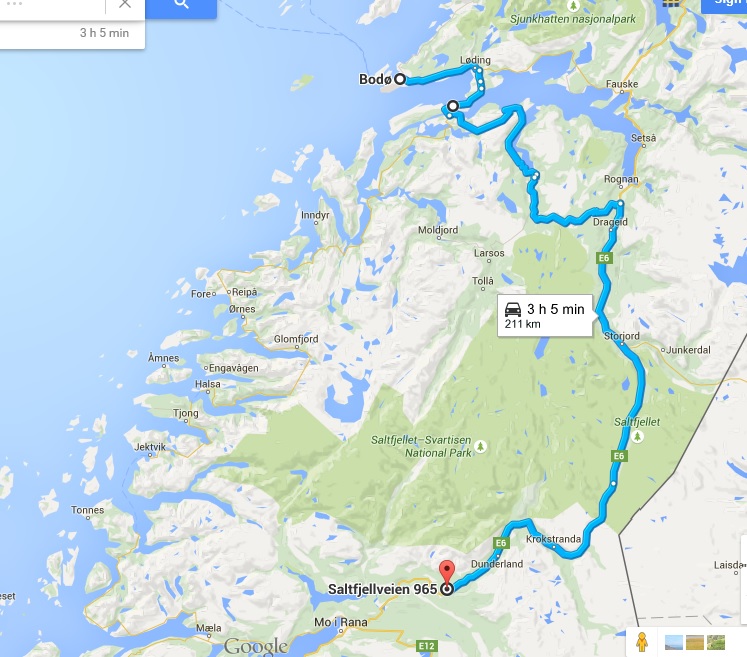

Upon arriving to Storjord I get the bad news: the road to Sweden via Junkerdal is — though not cut to the traffic — under construction on the Swedish side. Should I venture? Asking here and there I collect the necessary information: the route is a stony mess, all road metal of the worst stuff; several drivers have reported flat tyres. Therefore, no way! It would be folly with a touring motorcycle like Rosaura. Pity, because that’s a secondary route I prefer over this one, the E6, which is here quite busy, being Norway’s backbone from one end to the other. Between the north and the south of the country, only the E6 and a railroad exist.

I have to change plans and keep riding the E6 south towards Mo i Rana, where the next pass over the mountains branches off; but that means I won’t make it to Sweden until tomorrow.

As the route goes higher and higher, I’m once again, like a few days back, on a region where glaciers occur. There are several of them –rather small, though– on the peaks to both sides of the road. Landscape is here mostly barren, rocky land with tundra, and the wind blows cold: 11 ºC according to Rosaura’s sensor. After a while, there in the middle of this desolation stands a small shopping centre by a vast parking lot: it’s an Arctic Circle tourist trap. So, was I still in the Arctic? I had totally forgotten; but of course — now that I think of it — a large part of Scandinavia lies within the polar regions, and I’ve spent there a few weeks. But never mind. Be it welcome, for once, a tourist trap, because I am freezing and it comes in quite convenient for a warm up coffee and, why not, a photograph souvenir.

From here on the road starts descending slowly, glaciers are left behind, landscape gets greener, temperature milder and the wind — thanks God — eases off. Shortly before Storforshei (near Mo i Rana) I come across a farm offering accommodation: beyond the main building and the barn, around a wide lawn plot impeccably mowed, there stand a few rural cabins in great shape, neat, roomy and comfy. And the price is affordable. Do they take credit cards? Nope, only cash. But my last Crowns were already spent, since by now I should have been already in Sweden… No problem: the kind farmer accepts my Euros instead, and at a fair rate, too.

He’s a farmer in his forties, a talkative and likeable guy whose culture susprises me after a while of chatting. Talking about this and that, like for instance how much more interesting it is to study History at our age than when we’re kids at school, our conversation lands on the topic of blood mixtures and he tells me a curiosity: on northern Norway there are several villages whose people have mixed Spanish blood, because in earlier times there often shipwrecked Spanish fishing ships on the dangerous Norwegian coasts; the survivors –if any– had then to live for long periods of time among the locals until they had a chance to return to their homes, and some of them just got married and settled down. Particularly in one of those villages –he says– the tradition of siesta is still preserved that was brought there by those Spaniards.

As to the blood part, it can well be true, but this latter bit I don’t believe.

It’s time for a stroll, to which purpose I set on walking along a random path which, after a while, turns up ending on the road. Not far, I see a church’s peaked roof popping out of the treetops, and I aim for it. A church here, in the middle of nowhere? Isolated, apparently unrelated to any locality, it wears the evocative name of Neverness. Around it there is a graveyard with too many tombs for a place like this; and they’re not too old either, mostly dating from the past sixty years or so. I find it an intriguing and bizarre set.

Meandering among the tombstones I read a few random names. Peter Larsen Osterdal makes me recall Jack London. Why did the writer give this surname to his Sea Wolf? A dozen steps further, Albertine Storly and Konrad Habit Storly lay together, by Johannes Kristian Storly. How did they met? Albertine, the little Frenchy who married the Norwegian… What brought her here, or what took Konrad to France? How was their story? Each human life by itsel — I believe — is worth a novel. Now I come by Sophie Calbero, wife to David Calbero; this is not Norwegian, I suppose? Rather sounds Latin (I mean, real Latin). Was Calbero one of those Spanish fishermen? Then, Lars Kristian Larsen and Elias Larsen… Defintely London must have picked the surname from this country.

But it’s getting late and I’d rather go back to the farm, lest the dusk falls on me while in the graveyard of a church called Neverness…