Juan de Garay, conqueror and colonizer, third governor of Río de la Plata, explorer of Paraná river and fouder of Santa Fé and Buenos Aires, was born in Orduña in the year 1528. But before this event took place, the borough was to know endless disputes and rows for the sake of its possession.

Thus I wrote upon cosing the first part of this chapter dedicated to Orduña and, apparently, thus it happened.

The first documented mentions of this settlement date from IXth century and place it as already existing by VIIIth C, when king Alfonso I endeavoured for populating the region. Orduña -it is said- always belonged to its own inhabitants, and could have been founded in the High Medieval times, perhaps by Christians fleeing from Muslim invasions. If this is true, we’d be facing an eminently Castilian foundation, therefore only slightly related to the kingdom of Navarra, not to mention a Basque Country which, strictly speaking, has never existed, in spite of many of its contemporary citizens). The first defensive wall encircling Orduña was so thick that two carts could cross on top.

When trespassing this stone hall in the wall, if you close your eyes and adequately focus your senses, you can partake for a moment of the sensations of those who lived there millenniums ago; and even, with the help of some fantasy, you can hear the hustle and bustle of the old village: smiths hammering on their anvils, the bray of the donkeys, the hens clucking, the metalic noise of wheel rims on the cobbles, the peasants voicing their merchandise behind their barrows…

Notwithstanding Orduña’s ancient and seemingly autonomous origin, several centuries after its foundation it would lose forever (until recent times) its independence when king Fernando III, in 1218, granted to the Lord of Biscay, Lope Díaz II de Haro, the possession over the borough. The De Haro line, who weren’t lavish in names, christened their descendants with their father’s surname and, to the utter bewilderment and confusion of to-be historians, surnamed them with their father’s first name, thus forming a hereditary line worthy of some theatrical play. So, when the aforementioned Lope Díaz passed away, Orduña became his son’s, Diego López III de Haro, who in 1229 granted the village the same privileges as those of Vitoria (which served as a reference in such times and lands) and whom, upon ascending Alfonso X the Wise to the throne, gave up his serfdom to the Castilian monarch and went under the king of Navarra; though, willing to withhold by force what was given to his father as a grace, the Castilian troops had to suffocate the upraisal and recover Orduña.

Later on, by mid XIIIth C., Alfonso X himself authorized an enlargement of Orduña by six new streets, granted it royal privileges, different from the lordly ones it had, and gives them the monopoly over the commerce, thus acknowledging and promoting the growth in market and population that the village was experiencing.

XIIIth century was not gone when the Lords of Biscay (by then, Lope Díaz III de Haro, not to be mistaken with Diego López III, his father) return to disputes and set out their complaints to the Castilian king, who sentences like this “and about what thou say that Orduña must be yours and it was given by king Fernando as a grace to Don Lope and Doña Urraca your grandparents, truth is; but thou has made war from there and from there caused severe harm on earth, and privilege of Castile is that, if war is made from what was given by grace, and harm is done on earth, then Castile can take it righteously by force”, thus denying him the lordship he claimed. But after this king’s death, Lope Díaz III sook the suppport of Sancho IV (who was struggling with his nephews for the Crown) and made fast his power in Orduña and surroundings, granting it “entilement state of Biscay”.

Of course things were not to remain like that: once Lope Díaz passes away, the king Sancho IV recovers Orduña and, to reinforce such posession and to congratiate himself with its population, Sancho grants a new privilege to Orduña: an annual fortnight fair. By then a new, more ample wall is built, and the old one gets partly embedded in the church of Santa María. It is indeed stunning to walk around the church, more alike a fortress, and to watch upwards to its tall buttresses, its warlike patrol walkway and its sturdy impregnable walls.

Yet, Orduña’s misadventures had but begun. Taking advantage of Fernado IV’s minority, a new De Haro comes into play: he’s Diego López V, brother to the deceased Lope Díaz III, and he confirms the entailment state of Orduña subjected to the Lords of Biscay; but when he himself dies leaving no descendants, Orduña seizes the occasion for going back to the Crown of Castile, for the fourth time now; though not for too long: while dinastic struggles are held between Pedro I and Enrique de Trastámara, the latter delivers Orduña to his brother Tello, the actual Lord of Biscay. And though by 1370, after Tello’s death, the very lordship of Biscay is held by the king himself, Juan I of Castile, years later his heir Enrique IV confirms the privileges of Orduña and gives it back to the Lords of Biscay, who were now the Ayalas; besides, he exempts the village of paying taxes to the powerful Castilian stock societies and, finally, he grants Orduña the title of city in 1467, thus becoming the first and only population of Biscay with such a status.

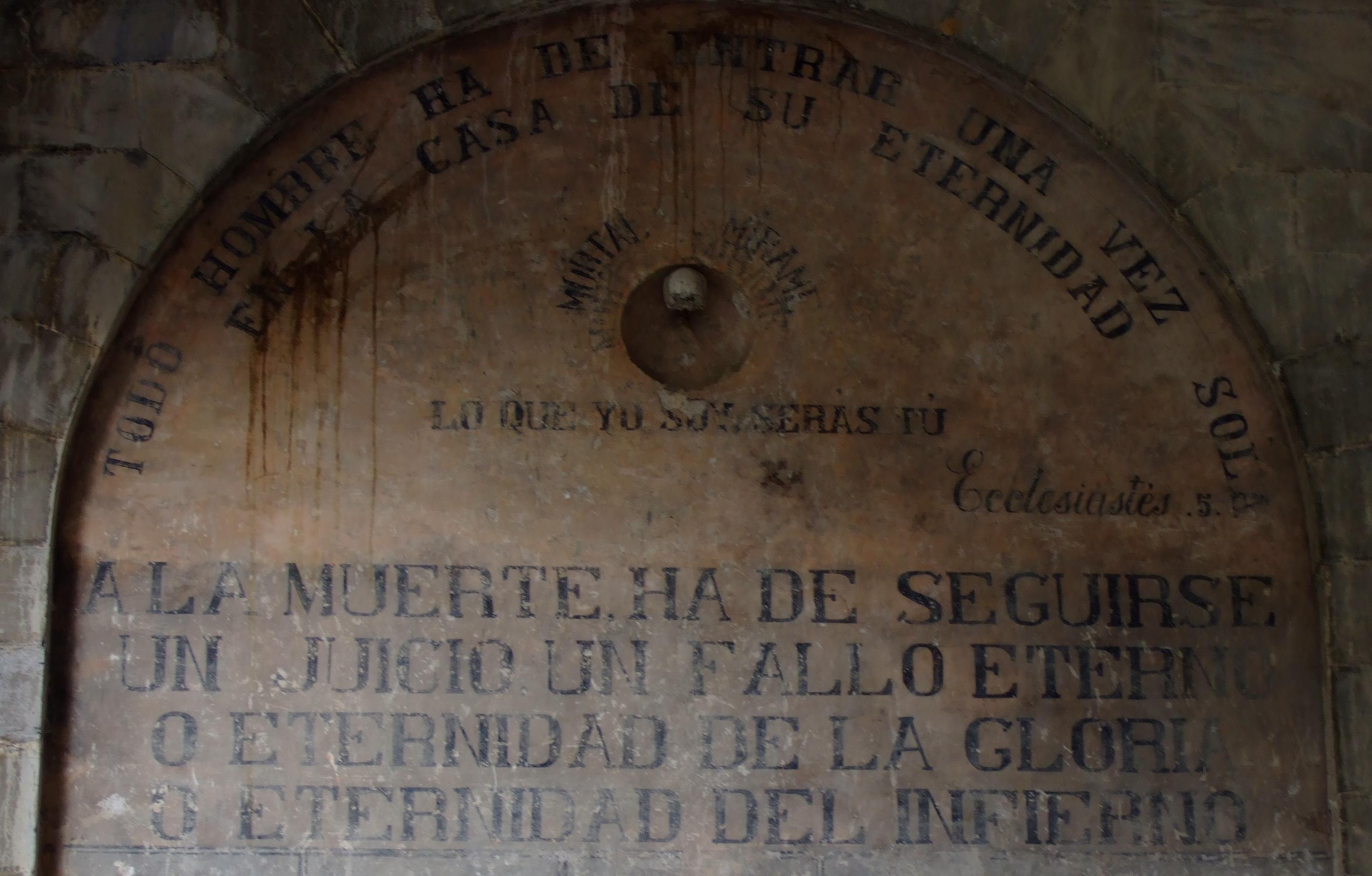

Dreadful legend under Sta. María’s portico: “To death a judgement must follow, a veredict eternal: either everlasting glory, or a hell everlasting”.

And here we are, dealing again with the ambitious house of Ayala, which we’ve already seen lording over boroughs and towns in other chapters of this series. The Ayalas first won a lawsuit concerning the posession of some of Orduña’s hamlets, with the help of Valladolid’s Chancery, and then the marshal García de Ayala gains from king Enrique IV the positon of Justice of Orduña; nomination that was later revoked by the Catholic Monarchs in 1476, not without violence, because Ayala didn’t accept such decision and was to be fought against. Four years later, among other several provisions on Orduña’s behalf, the Monarchs ratified that the city would never again be parted with the Crown, nor its posession given away, they also revoked any mercy of Orduña granted to the Ayalas and granted its defense and its hamlets’ against the marshall and his son, who continued keeping the mayoralty of the castle; and these two, though being forgiven the uproars when trying to get hold of Orduña, they were commanded to pay a high sum “for the evil it had got by their cause”.

Meanwhile all these ups and downs took place, Orduña had experienced a second expansion thanks to the commercial situation derived by the increase in merchandise contracted between Castile and the Cantabric harbours: once more the city walls were broadened, encircling now the market square; however, when all struggles for the Orduña’s posession seemed to be settled, along with an economical prosperity without uproars, in 1535 part of the city was destroyed by a fire, and its importance declined in the region. Worth mentioning is the customs building, outstanding for its architecture, soundness and situation; built in 1793 costed three millon reales.

As anyone can see, Orduña’s history has little to no connection with Navarre or Basque Country. Its recent basquism is only a matter of political interests (which are, after all, economical interests). But what’s more important yet: anyone can see how absurd is to maintain nowadays privileges whose goal disappeared centuries ago: they were decreed for stimulating population of certain regions and, once this was achieved, the privileges lose all sense; worse yet: keeping them today implies an unfair discrimination against the rest of Spanish regions.

And now, reader, if you’ve stood fast this far, following me along the meanders of Orduña’s history, its repeated and mingled stages, the ceaseless serfdom shifts, I’m sure you won’t mind if I guide you along the other meanders: those bends of the road that take us to its beautiful surroundings, most of all if you’re a motorcycler fond of bends and landscapes; because Orduña enjoys a privileged scenic situation, right in the middle of a wide oval valley, fertile and splendid (as the historian Madoz put it), among high and precipitous hills of a unique natural beauty.

First, taking a stroll along town, we can find this lovely corner that seems to be anchored in the past; this huge ramshackle house that was perhaps a mill -as it’s erected by a stream- or maybe a guest house, or a farm, and which now looks neglected, inhabited only maybe by ghosts of our great-grandparents’ times.

These windows are also an example of the austere and practical architecture of yore, when people lived mostly in the open and bedrooms were for just sleeping, thus light not being particularly appreciated.

This one is just a nostalgic shot for me, totally meaningless for you: a school of the Compañía de María, a nuns’ order ruling many educational centers in the past century. My sisters used to attend to one back there in our early childhood, when time didn’t exist at all, and the skies always shined a whitish blue, with that special light of the cities in the south, by the sea; a light that forced me to always keep my eyelids halfway closed.

Once out of town, if we keep riding south along the same road we came in, we soon start climbing the steep slopes and U bends going up, up the almost vertical hill of Sierra Salvada until, once upon the summit, we arrive to the province of Burgos. From up here you can behold the most scenic view of all: the green fertile and handsome valley of river Nervión where the founders of Orduña laid their craddle, a treasure coveted by endless kings and lords one after another for generations; sheltered, temperate and fruitful, where such wines are elaborated that may well outstand those in France…

What now remains to be said? We’ve been together along the best of Orduña: the roads, the landscapes, the history, the streets. It’s time for a farewell á la Rosaura (my motorcycle): some good pinchos and a superb wine, of the local kind called chacolí.

That’s all, folks!