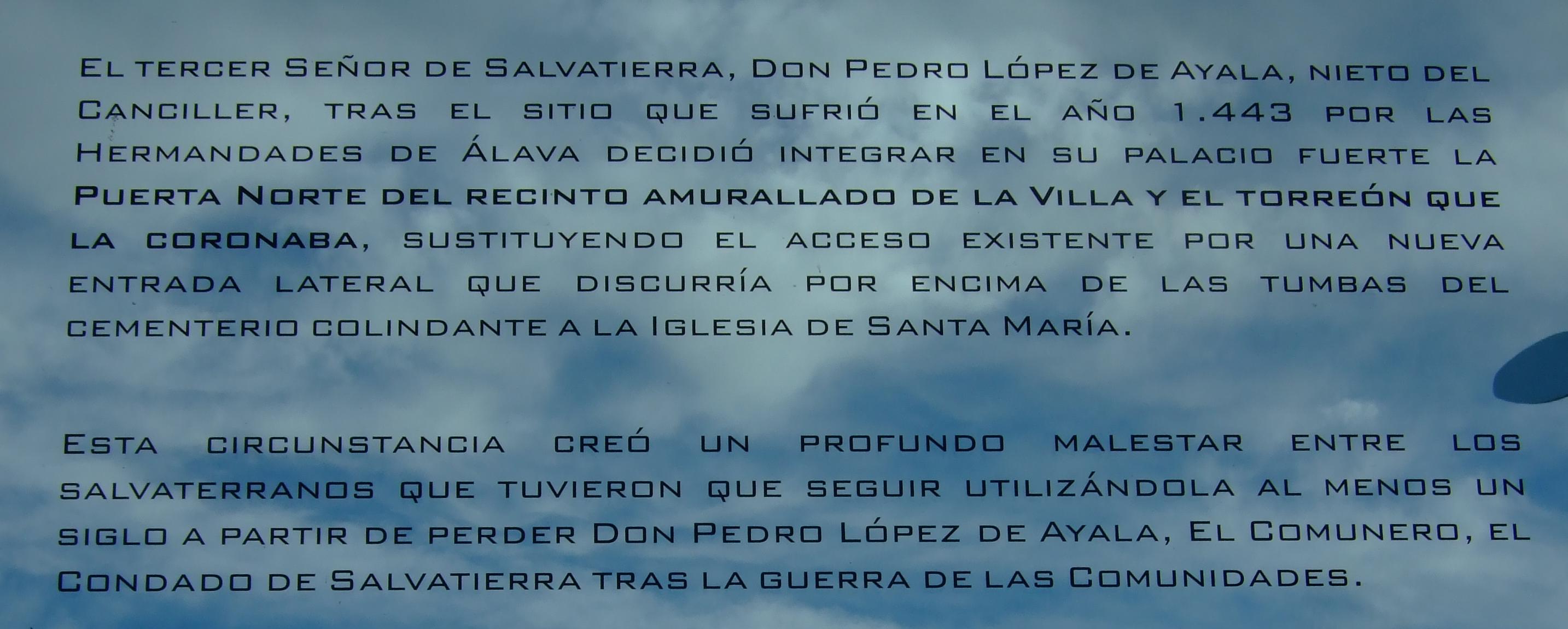

Right after arriving to Salvatierra from Zalduendo (described in a previous chapter) and parking the motorbike inside the walled borough, I come across this curious though misleading legend exhibited by St Mary’s church, near the wall’s North gate; misleading because both narrated events (how the gate become part of Ayala’s palace, and how the comunero lost his earldom) happened within a century’s difference, not everyone knowing that Don Pedro López de Ayala el comunero in the second paragraph of the inscription is not the same as the Pedro López de Ayala mentioned first, but his grandson. Actually, there were a whole line of Pedro López de Ayala succeeding each other and inheriting Salvatierra’s rule along cc XVth and XVIth. So, trying to solve this little puzzle, I start ranging the Loyal Villa of Salvatierra.

Each time I visit one of these villages I amuse myself with imagining its evolution, how it was founded, how it grew, which were the circumstances; and I fancy looking into the past with the eyes of my fantasy, imagining possible scenes of its history.

Going back to c. Ist bC, I see the Romans moving forward along Hispania and coming across a small shepherds’ settlement of basque natives on top of the knoll where now Salvatierra stands. These troops would report Rome of what they were exploring, and a few decades later Rome builds along such place the XXXIV route ab asturica burdigalam, connecting Astorga with Bordeaux. This is one of the mainstays for making Salvatierra become an important place in future. There is evidence of Romans remaining in the area as late as Vth c, aD. By then, this was the border between the Earldom of Vasconia and the visigotic Hispania.

It might be that Navarre kings had founded, in 824 aD, a tiny village whereon the nomad shepherds’ settlement was, giving it the Basque name of Hagurahin (farewell place), and this village belonged to the crown of Navarre until 1200, when Alfonso VIII of Castile conquered and annexed it to his kingdom. Since then to the present (except for the past decades), the village has been Castilian.

As Castile wanted to strengthen its borders and stablish commerce roads between Rioja and the sea, a few decades after conquering Hagurahin, in 1265 to be precise, Alfonso X (the wise) founds on Hagurahin a new borough called Salvatierra, grants it the privileges and disposes that a protection wall should encircle it. Within the walls, it will be given the characteristic layout of other borouhs in the province, like Antoñana: three parallel long streets running N-S and connected y lanes, with a stronghold-church on each end.

Consequently, soon the borough would grow and prosper, turning into a strategic crossroads: the East-West route between Navarre and Astorga, and the North-South route between Rioja and the sea.

I stroll the place following the landmarks with historical information, strongly biased in an anti-Spanish way, that can be read on the most relevant places; and with such information I can, more or less, replay the events of this borough’s history.

In the year 1367, under domination of king Enrique de Trastámara, Salvatierra was invaded by a powerful army lead by the legitimate heir of Castile’s throne, Pedro the Ist, nicknamed “the cruel” by his enemies and “the righteous” by his followers. He marched on Salvatierra along with the armies of several allies from other nations, like the famous Black Prince, Earl of Lancaster, French, Navarre and even Jaime the IIIrd of Mallorca. Confronted by such a numerous army, Salvatierra gave in without battle.

Pedro the Ist wouldn’t outlive his own victory much longer, dying two years afterwards. His heir, Juan the Ist of Castile, bestowed Salvatierra as entailed estate onto Chancellor Ayala, who passed the privilege to his heirs for four generations. But the Villa de Salvatierra was never too fond of this Ayala lineage. It was the grandson of the Chancellor, Don Pedro López de Ayala, first Earl of Salvatierra, he under whose dominion, in 1440, the deeds narrated in the first picture’s legend took place: how he enclosed within his own fortress the Villa’s North gate, forcing his vassals to enter the town stepping on the graveyard’s tombs, where their ancestors laid.

One century later, in 1520, the third Earl of Salvatierra, grandson of the former, who was bond to the Comuneros (a movement opposing the king of Castile), commanded his vassals, the people of Salvatierra, to contribute with a levy of three hundred armed and well equipped men to rise up against Carlos the Ist, and told them to disobey any order coming from the Brotherhood of Álava. However, the people paid no heed to the Earl and, during the Comunidades war (between the king and the Comuneros)Salvatierra didn’t fight the king, but their lord. López de Ayala tried to siege the Villa, but its inhabitants defended it, so that it could be taken by the royal troops. The Earl, defeated and imprisoned in Durana, was stripped of his possessions and Salvatierra passed under the direct rule of the Crown. In December 1523, Carlos I, in reference to the provided support to his cause, rewarded Salvatierra with the title of Loyal, dismissed the last Pedro López de Ayala, arrested him and deprived him of his Earldom. This Don Pedro died captive during 1524, though there are some doubts as to the circumstances of his death.

Lone window opened through the wall. Some gallant must have spoken love words to some maid behind the grill.

While reading and taking pictures I don’t feel the passing of time as I discover the nice alleys of this important medieval borough. Yet, some tragic events remain to be learnt. I stop for a while in a small square shaded by six thick trees and, sat on a bench, I read the history of Salvatierra while tasting a txacoli (white sparkling wine typical from Basque country) and a pincho.

Despite the surrender agreements, Salvatierra wouldn’t get rid off its serfdom so easily: some Don Atanasio of the Ayala lineage claimed the village as his due possession, and a lawsuit was held for over forty years until, in 1569, it was finally sentenced that Salvatierra was free. However, there were yet some other tragedies to undergo, much sadder by far. First the bubonic plague made its presence in the village, and then, in August 1564, a vast fire burnt it down during twenty four hours, leaving but ashes, the two churches and just one civil house, the now called “House of widows”. Both churches’ windows and doors had to be bricked up because of the stench from the corpses. Livestock commerce and traffic was forbidden across the walls. But the plague managed to come out the village, killing 40% of the population.

In contrast with the villages I’m visiting in the North of Alava province, this region to the South is more alike Castile, though it belongs to the Basque country. You can hardly hear Basque spoken around here, despite all the trouble taken by the Basque governments for promoting this primitive language, called Euskera by the natives. Which is only normal, because for centuries since the South Álava was conquered by Castile–perhaps even before that–the Basque speakers slowly and willingly gave it up and switched to Castilian, as Euskera was considered gross and uncouth. There seems to be no trustworthy source–definitely, not the speculations of the anti-Spanish propaganda–regarding when that happened, but one can guess that, after five centuries coexisting with (and perhaps dominated by) the Romans, plus almost one millennium ruled by Castile, Basque language must have been neglected along the early middle ages. In a 1970 poll produced only three native Basque speakers in and around Vitoria. Thus, Basque revival in Álava turns out to be a totally artificial move, serving political aims rather than originating in historical roots. And so is the new official name of Salvatierra: Agurain, chosen to bestow the village with a Basque flavour that it has not had during the past nine centuries. Such a political decision, as proves the fact that not even Juan Perez de Lazárraga, Basque language poet and writer, ever used the word Agurain for naming Salvatierra.

Sun starts traveling down. I’ve been roaming along Salvatierra for hours now, I’ve walked all over its walls, inside and outside, and I’ve peeped into the shutters ajar of old buildings, smelling gloom, rank and damp. I believe that many of these basements still sleep untouched in the lethargy and the echoed silence of medieval times.

As a digression, as I get to know better the Basque country and its history–so biased, in general, by brainwashing pamphlets and “information” boards–I wonder about two facts: one, many (if not most of) towns in Álava show big pride in the regional laws granted (magnanimously) by the kings of Castile, while rejecting any cultural connection with Castile and reclaiming their belonging to Navarre, whose crown never granted them anything, except for ratifying those given by Castile. Two, they claim their total independence as a country whereas most of their aspirations are based on their having formerly belonged to Navarre. Wouldn’t it be much more logical to reclaim their inclusion within Navarra?

And there’s one more fact, seemingly chance, which I now believe takes its origin in a well thought project: in the heart of most villages and towns, often neighbouring the city hall and always at a visible place, there is some or other herriko-taberna (people’s tavern) showing onto the front several etxeras, the symbol used by those ETA (the Basque terrorist organization for independence) supporters who ask for the “rights” of ETA prisoners and demand them to be transfered to prisons nearby Basque country. These herriko tabernas, seldom offering good pinchos nor service, must needs be financed by the city councils supporting ETA, or otherwise they wouldn’t stand the competition in such privileged spots. Just a guess.

To day, Salvatierra is a nice borough easy to walk and know, and the tourists will sure enjoy their visit here. The two majestic churches at both ends watch the quiet streets (thanks to the wise and severe traffic restrictions), tidy and well taken care of, full of amazing houses and palaces whose fronts show superb coats of arms. A few small squares provide a medieval touch and the colonnades of Zapatería street, built so that a horseman can ride underneath, give it a noticeable authenticity. And, of course, there is no shortage of bars and restaurants offering more than enough variety of atmosphere and design, a tempting selection of tasty pinchos, which are the pride of the Basque country, and the regional sparkling wine called chacolí.

I walk slowly back to the North gate, where I left Rosaura. Halfway I perform my own Basque trail ritual: a chacolí and a pincho. It’s a nice warm pub, furnished in wood, whose kind barman serves the wine on a chilled glass and the pincho on a warmed up dish. When I’m done, I keep walking towards Saint Mary’s church. My shoes’ rubber grinds on the cobblestones. Before getting on the BMW I cast a last look to the once Loyal villa of Salvatierra, now simply Agurain, not loyal any more to Castile. The sun is setting, and just touches the sturdy walls of Saint Mary’s stronghold under the blue sky.