When the traveller driving south from Egilsstadir along the famous Icelandic Hring Vegur (the Ring Way) reaches the solitary mountain pass dividing the northern and southeastern basins, there appears before his eyes a magnificent view; but also a dismal one: for the first mile from the pass towards the impressive glacial valley, the road has a very steep slope that, being dismaying enough on its own, can get also quite slippery. If, besides, you’re driving an unreliable and unpredictable car, the hair-rising fear of plunging into the abyss is hard to escape.

After the incident with the fan, for long and slow minutes we proceeded downhill with extreme caution, engine-braking, holding our breath and knocking on wood, lest our shoddy Polo decided it was the right time for a break failure, or the steering wheel broke down when in a hairpin turn. But nothing of this happened, obviously, or I wouldn’t be writing this now. The incline became gradually softer, and eventually we were again able to enjoy the astounding environment.

Farther on we reached the flat wide valley-bed and drove along it until we finally arrived to the ocean at Breiddalsvik, from where–and almost until the end of our trip–the road would run skirting the coast, therefore entirely at sea level.

However, together with the warmer temperatures and no longer fearing snow dunes, there came the second worst enemy of the arctic driver: the wet snow, an annoying layer of half melted ice, a semisolid that, like when driving on sand, severely and unevenly hampers the wheels’ advance on the road, making also for a lesser fuel autonomy and a difficult and dangerous steering. Actually, and depending on the wet snow consistence and the road incline, the tyres can lose grip and the car get stuck.

And indeed, we had a lot of that stuff from the moment we reached the ocean and along the whole coastline skirting the deep fiord, until we arrived to our first planned stop for that day: the lovely, peaceful, tiny little fishing village of Djúpivogur. Fortunately, though the wet snow slowed down our advance, we didn’t have any mishap and we could enjoy contemplating delightful landscapes we found on our way along the very scenic Berufjordur…

…and also one very pictoresque thing we hadn’t seen before: a traditional fish drying-place, consisting of several wooden structures where the beheaded fish is hung from the beans by the tail.

Located at the tip of a small cape, sheltered from the rough southwestern seas and the cold northwestern winds, the fishing village of Djúpivogur is a privileged one, with its romantic little harbour well protected, an facing the rocky peaks right across the fiord.

Behind the harbour and Djúpivogur’s scattered few houses, the bleak pyramid-mount of Búlandstindur keeps an eternal watchful eye on the village.

As it was about time for lunch, we decided there couldn’t be a better place for a meal than this fishing community. There were only two eating places in Djúpivogur: the hotel and the shop; so, deeming the first one would probably be too expensive for our budget, we chose the second. It was a fine local, two-in-one, combining a small convenience store and a modest but cozy restaurant, featuring four or five tables and huge windows facing the harbour which provided for a splendid and relaxing view. Of course we ordered fish and of course it was delicious, so that we leisurely enjoyed a very nice meal, tasting the fresh food and the view at ease: the snowy mountains lit by the sun, contrasting with the marine blue sea and rising above the few small boats which dozed on the harbour’s calm waters.

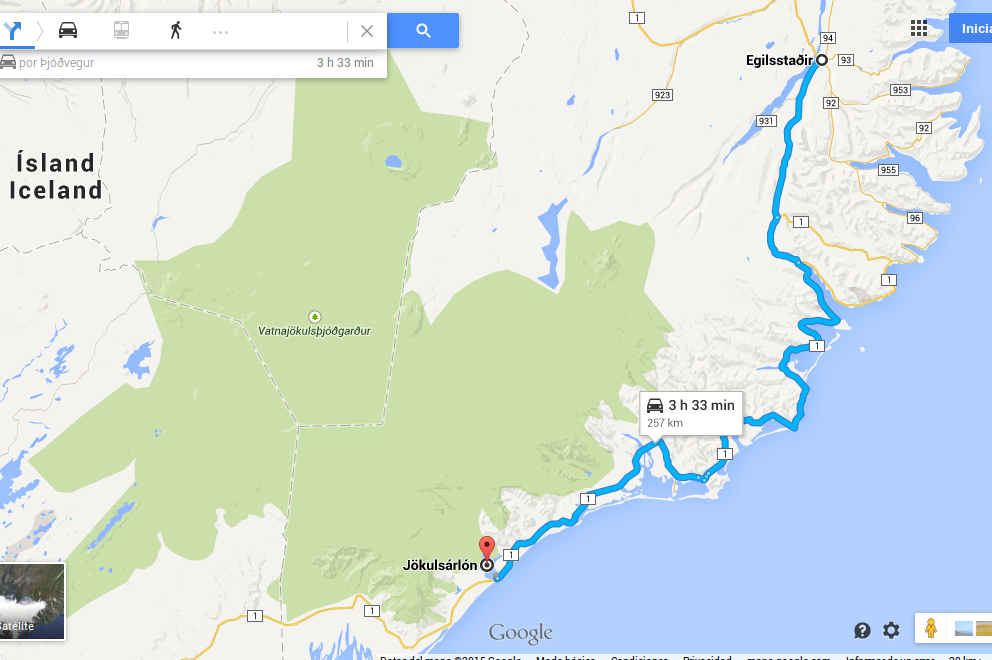

When checking the weather forecast update for the evening, we got a confirmation of the news in the morning: starting from dusk there would be snowfalls. So, though we still could count on a few hours of fine weather, we didn’t know if that was enough for properly visiting the glacier lagoon Jökulsárlon, allegedly one of Iceland’s highlights. Should we then hurry up and try to get there today, or rather take our time, driving at ease, and visit it the next morning after spending the night in Höfn, 80 km away from Djúpivogur? There was no easy answer, but being so hard to make reliable plans in Iceland–with the changeable weather and unpredictable road conditions–and driving an even less reliable car, we just opted for driving without any expectation nor hurry and take decisions on the go. Fortunately there were three alternative youth hostels where to stay overnight, plus no shortage of–more expensive–guesthouses to take into account just in case.

And indeed, what an amazing climate change we experienced!: no sooner had we left the sleepy Djúpivogur than, after the first turn of the road, we found ourselves like if in another planet–nay, like if back to our planet: suddenly the weather got mild and sunny, and the landscape snowless.

It’s noteworthy to say that many of the mountains along this part of the road are flanked by bare, gargantuan masses of loose boulder, broken and crumbled by erosion and the force of ice, then spilt from the rocky heights. These stones are naturally piled with the maximum possible incline (around 40º, as engineers well know) in a very unsteady equilibrium and, when looked at up from the mountain’s foot, they cause a strong dizziness, making us feel like if we’d fall upwards. As a matter of fact, slides are very common in that region, and it’s frequent to find some of the boulders invading the pavement. Looked at a distance, this mountains resemble the hoofs of a colossal ungulate.

So, well, as by the time we went past Höfn it was too early, we kept driving, with the hope of making it to Jökulsarlon on a fine light. By the way, this is the part of the island where better and closer the glaciers can be observed from the highway; oh the glaciers!, those accumulated and compacted snow masses, spilling down the high peaks along the valleys in breathtaking tongues of ice, with their hypnotizing blue hue.

Thanks to the setting sun and the cloudless sky, we weren’t short of delightful scenery…

Yet another awesome landscape[/captio, broken and crumbled by erosion and the force of ice, then spilt from the rocky heights. These stones are naturally piled with the maximum possible incline (around 40º, as engineers well know) in a very unsteady equilibrium and, when looked at up from the mountain’s foot, they cause a strong dizziness, making us feel like if we’d n]

…until we finally reached the magnificent Jökullsarlón, the glacier lagoon, where one ohypnotizing blue huef the largest arms of/strong the inmense VHowever, together with the warmer temperatures and no longer fearing snow dunes, there came /patnajökull glacier dies, right by the sea.

Satellite view of the glacier tongue dying in Jökulsarlon

There we parked the car, walked to the shore, then got stunned: we had gotten there at the right time for witnessing one of the most spectacular phenomena one can behold: the tide strongly flowing in through a narrow channel into the lagoon and lifting the massive ice blocks sleeping there.

The tide flows in, fills the lagoon and melts the ice

The tide flows in, fills the lagoon and melts the iceThis is a short video giving some approximate idea of how striking this phenomenon is:

We could only hold our breaths at the sight of this astonishing scene; the agony and death of ice that had been formed perhaps 10,000 years ago.

At the flood of tide the comparatively warm sea water gets into the lagoon, soaking and melting the big rocks of ice. If the tide is strong, the inlet of water through the channel is very swift and powerful, resembling a river flowing inland. Benito and me could see this dark-blue sea river splashing against the icebergs and diving underneath them in vortices, pushing them backwards, moistening them and changing their thick translucency into a light transparency; and so the big blocks get cracked and split into smaller pieces.

Here’s another video of this curious flow:

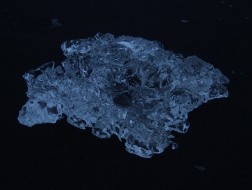

Then, at the ebb of tide, the water retreats from the lagoon back to the ocean carrying out those ice blocks that melted down to a size small enough to pass through the shallow channel; and lastly, the low tide gently places many of those blocks, “carved” to beautiful capricious sculptures, onto the black sands of the beach. Thus, all year long for over endless centuries, twice a day–with every flow of the tide–the sea takes a bite of the glacier and swallows it up, claiming what is his; after a cycle of ten thousand years, the sea returns the frozen water to where it belongs: the eternal ocean.

The remnants of what–for ages–was a proud glacier lie now on the beach, exhaling their last breath; natural beauty until the last minute, they embellish with their gem-like carved surfaces the volcanic black sands, in scenes so bizarre they seem unreal.

I couldn’t help bitting and swallowing a piece of such ice. It was like eating up the prehistory: putting into my body some molecules that had been deposited during the past then thousand years.