On asking the employee in the Reykjavik tourist office what there is between Mývatn and Egilsstadir, i.e. the upper leftt quarter of the island, he had quickly replied: Nothing; and then added: but it’s a beautiful Nothing. And it was a splendent sunny morning when we set forth for this beautiful Nothing.

Though far from being perfect, the repair job we had done to the car was effective enough to keep the engine at a reasonable temperature despite the cold outside, and this sufficed to keep us reasonably warm inside–as far as there were no blizzards nor fights against the snow. In this way we drove for some hours throughout whitey landscapes, the ice crystals reflecting with violent radiance and one million shines all the light of the gleaming sun above.

Godafoss means waterfall of the gods. Well, perhaps the Icelandic gods have a preference for dreary and sinister whereabouts, but to us this dismal ice-age corner of the world could have rather been named waterfall of the demons.

Oh!, sorry: this is an old picture of the same place, I confess. But I don’t want to cheat on the reader. By the time we arrived to Godafoss this day, this is more how it looked:

Icelandic winter never stops surprising the beholder with bizarre exhibitions:

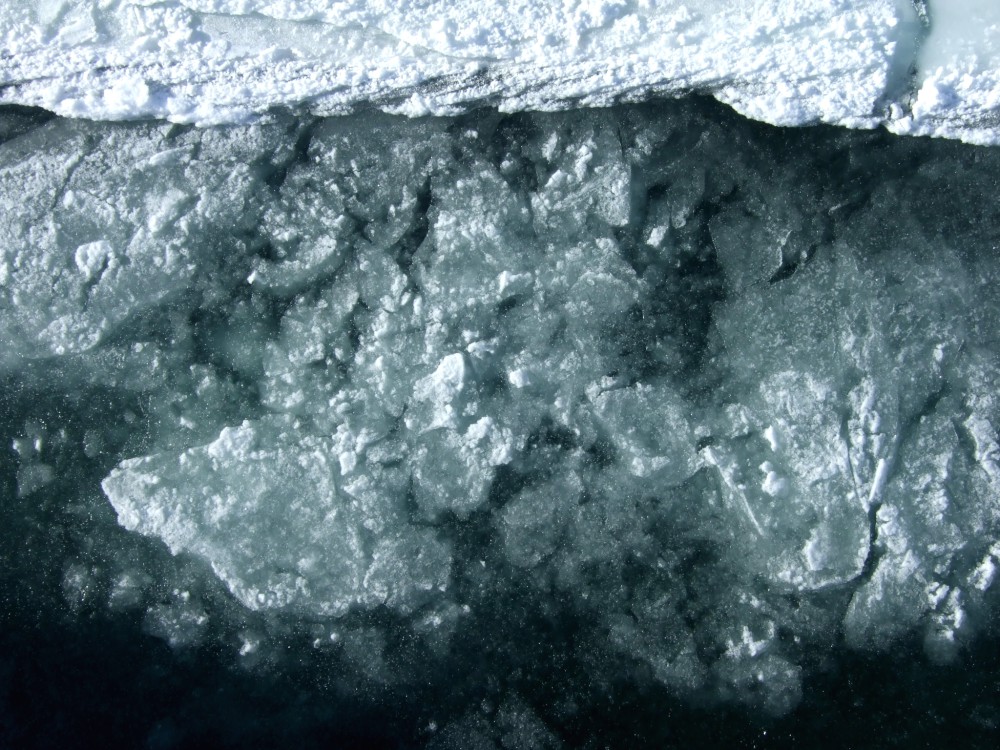

It wasn’t until mid afternoon that we arrived to the active volcanic region of lake Mývatn, with its craters, steaming grounds and geothermal waters. At this time of the year, the lake is frozen.

But only at some kilometres’ distance we found quite a different type of lake, steaming and perfect for a bath in a natural hot-tub:

And in Iceland there is always natural beauty beyond every turn of the road:

Also we saw some shows of the power underneath:

Along the Ring Road, driving clockwise, lake Mývatn resort is the last enclave Icelanders have gained to the hostile volcanic island; and there is a dramatic contrast between the life-rich soil and warm enjoyable waters, to the west, and the barren, desolate stony highlands that lay beyond, to the east: one hundred miles of just lava, snow, rocks and icy waters: the beautiful Nothing. The inmense grandiosity of the white desert.

And it was in this beautiful Nothing where we had our share of adventure that day. As the afternoon was going by, the sky got darker and cloudier. The infallible Icelandic Weather Service had forecasted some light snowfall for the region, and as most of the road runs along highlands, while driving we pored over the mountain passes in our map, accounting every single metre we gained in altitude, afraid of being caught in another of those terrible blizzards like our first day, or simply afraid of getting trapped in any of the many sudden snow heaps along the road. Taking into account that virtually no trafic goes that way, getting stuck in the middle of nothing (no matter how beautiful this Nothing is) could have tragic consequences. Well, at least we had learnt a vital lesson two days ago: to always drive with a full tank in chill weather, so as to, in the case of an accident forcing us to spend the night onto the wild, we could at least leave the engine running and thus have some heating.

There were two passes we had to go past, though we didn’t know exactly how high, our map not providing detailed information. When approaching the first, the wind got stronger–as expected–and we saw again the awesome but dreary sight of dry snowdust blown across the road, and soon we came by the first snow heaps on the road shoulders, when not right in the middle of the pavement, which shrunk our hearts every time. What makes them so fearful is not so much their size or scope–as most of them sit on one side of the road and cars can drive past the mounds pulling to the other side–but their unpredictability: you can find them anywhere: round a bend, behind a foggy stretch or–the easiest–camouflaged with the rest of the white or even the snowfall itself: in conditions of very diffused light, shapes totally lose their reliefs and our sight can’t have any reference; it’s like becoming blind, our sight sense gets completely fooled and all our eyes can perceive is a uniform depthless curtain.

And, as such was the case, for an anguished while we drove with extreme care, and our nerves only got some relief when we noticed the car was rolling downhill, which meant less chances of back luck. So we congratulated ourselves and felt in the mood for even joking. First challenge passed! Now if we could only get over the next mountain pass, the worst stretch of the evening–and our fears for that day–would be gone, because after that there was the coast, with better temperature and way less dangers. Or so we thought, at least. Also we had some reason for optimism, because–according to our map–the next pass, second and last one of the day, was lower than the first. And indeed we drove it without any further drawbacks; so when we finally saw the dark-blue ocean after a turn of the road we really gave vent to our relief, celebrating our success with almost hysterical expressions of joy.

But this wouldn’t last long, because soon afterwards an indicator in the dashboard started flasihng red, telling us that something important had got broken again in that crappy Polo: it was the alternator lamp, meaning it was not generating electricity. When this happens, the only electrical supply for the car lights and engine spark plugs to work comes from the the power accumulated in the battery, but as this is not getting recharged, there is only a limited time for everything to keep running before–once the accumulator gets drained–total comma of the car occurs; and then comes the freezing cold, and darkness befalls…

And how long is this limited time? We didn’t know. My guess was: no less than fifteen minutes and no more than one hour; but really, no clue. Our scheduled destination for that day was Reydarfjördur, where there is an affordable youth hostel; but that town was fifty kilometres away, which–considering the slow average speed we could make on such roads–meant a one hour drive, more or less. We might risk it, but it was too hazardous, as we didn’t have any guarantee the battery would last that much. So, we ought to give up on Reydarfjördur. Actually we’d be lucky if we just could get to the nearest town, Egilsstadir, around fifteen kilometres from our position. So we switched off the headlights–despite dusk was getting closer–lest they helped drain the battery too fast, and we gloomily (pun intended) drove on, yet hoping for the best.

Fifteen minutes later we were crossing the bridge in Fellabaer and headed the long straight leading to the street lights of Egilsstadir. We were reasonably safe for that evening.

But what then? Deliberating about our next steps on a running engine meant wasting precious electrical watts we might need afterwards; but on the other hand, stopping the engine might mean even more watts later on, as every time you trigger the starter it sucks the battery badly. Whatever we were to do was to be decided now, without delay. So, well, we pulled the car by a supermarket’s lot and stopped it there, took a look under the hood and needed only five seconds to spot the breakdown: the alternator belt was gone. Considering how long cold climates preserve belts’ rubber, the thought came to me that it probably had not been replaced for over at least one hundred thousand miles; actually, perhaps it had never been replaced during the whole car’s lifespan. How irresponsible! We were totally mad at the company, and our first impulse was to dump the car to the ditch and leave it there. Definitely, some very serious talk with the manager was required, if not a full denounce in the nearest police station.

On the other hand, looking at it from a positive perspective, we have to admit we had been very lucky. According to our travel book, Egilsstadir was the service town for east Iceland. So, if there was a place where we could find a mechanic and spare parts, it was Egilsstadir. Therefore we had had the breakdown in the best possible spot of the road that day (if there is any good spot for a breakdown). And indeed, when we walked to a nearby petrol station, the tender told us that there were two guesthouses and two car workshops at a three minutes’ walk from there. Yes, that was lucky, and we couldn’t have asked for more. One of the guesthouses was located in the same building as one of the workshops; so we took a room and telephoned the rental car guy, who upon our complaints agreed on paying for our accomodation that night (and of course the repair); which was the least he could do, honestly.

Thus arranged, and though a bit frustrated for the dire straits we had gone through, we devoted the rest of the evening to tranquilly enjoying ourselves the best we could. We first ate a tasty and nourishing mushroom soup for dinner, then took a very long walk along the road in the still night, and finally drunk a couple of well deserved beers in the clean quietness of our room, after popping in and out the local bar, which was desertic. Despite all and the nuisance of not being able to visit Eydarfjördur, we couldn’t stop congratulating ourselves for our really good luck. Another relatively happy end to an eventful day.