Santo Domingo de Silos has been unforgettable and hard to beat. Little did I know, when I decided to spend the night there, how would I be rewarded. The snug and cozy village, the natural and pristine surroundings, the peaceful and quiet atmosphere, the hearty and courteous neighbours, the perfect climate … Not a singe discordant note in the melody.

The afternoon of my arrival, I went out at dusk to check on the bars and get me some dinner. I pinged two or three, until I found the restaurant. The landlady was having dinner at one of the tables and, the moment I got in, asked me, “how can I help you want, son?” I said I wanted dinner and she offered me a menu for ten euros, in quite a motherly way, asking me what did I want as a starter, and as a main dish, what for a desert and drink; like in those inns of yore. Castilian soup and fried eggs with morcilla de Burgos would do, then. I sat down and, before going into the kitchen to place the order, in the most natural way she handed me the wine bottle half full the former customers left off: “here -she said-, you’ve got more than enough, but feel free to ask more if you want”. I love this Spain without complexes nor fuss, no French-like frills, which you can still find in some regions. And I dined like at home, comfy and sheltered. And I reckon I was not alone in feeling comfortable there, because the place was hopping while other restaurants looked half empty. There were some froggies at a neighbouring table, and another couple probably Dutch or Germans, by their accent. There were also some locals, I guess, because they knew the lady and the waiters. A warm and friendly atmosphere, in short.

When I came out it was cooler and, from outside, the restaurant looked even more inviting: like those Christmas cards where, contrasting with a snowy landscape, the warmth in the homes is symbolized by the yellowish light coming out the windows. There was hardly anyone on the empty streets; other bars had already closed. The church bell was tolling a quarter when I walked by its wall. It was already compline. That night I slept like a newborn, lulled by the gurgling of the water on the stones of the brook. My last thought before falling asleep, overcome by fatigue, was the decision to extend my stay another day.

And not far from where I was resting my head must have rested his, almost one thousand years ago, Don Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar. It is said that The Cid, in his exile, spent the first night in Silos; and according to historical documents he seems to have made personal acquaintance with Manso Domingo (the to be Saint who gave his name to the monastery and the village) when the latter was but the abbot of the former monastery in Silos, called San Sebastián. Whether both things are true or not, historians will tell, but the legend certainly contributes to the mysticism of the village.

However it be, there’s no doubt that Rodrigo Diaz owned some country state within Peñacoba boundary, now a district of Silos; and after that route, “the banishment of The Cid”, I went next day on a pilgrimage to Peñacoba along an ancient and evocative path, passing through a labyrinthine limestone landscape where only grow aged and hard-wearing savins.

By the way, I finally didn’t spend two nights at Silos, but three. I was so at ease that I couldn’t make up my mind for leaving. The surroundings of Santo Domingo are as pastoral as the village itself, and when sauntering around it seems as if the so called “progress” had not yet arrived to this nook of Burgos: stone buildings, clay tiles, wooden post fences, bridle paths, spread out cattle… In some places, almost nothing reminds the visitor of the century he lives in… but for the cars.

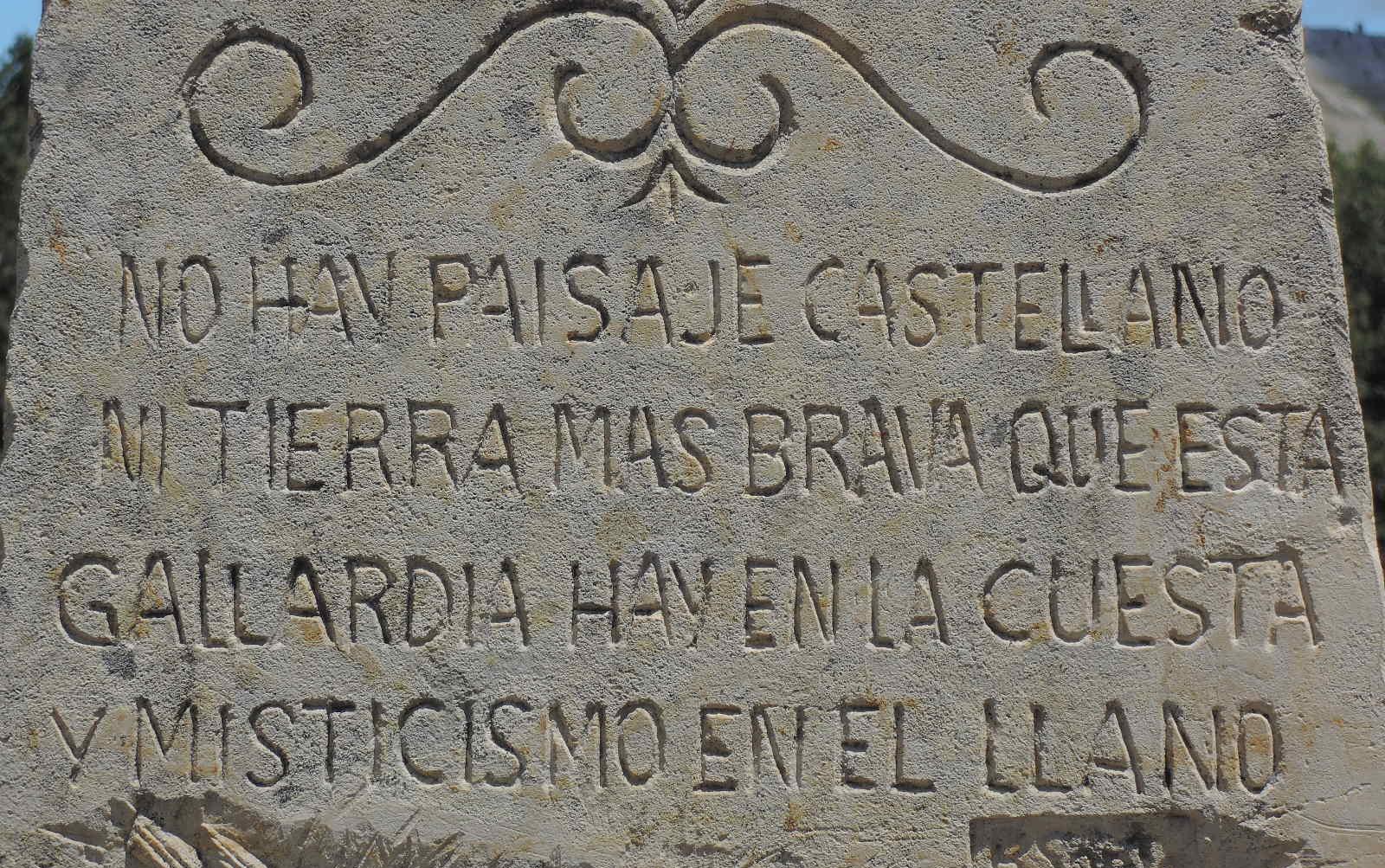

In another of these routes, when surmounting a hilloc after a long and tiring way, at the side of the road and facing the splendid panoramic view of the pure and hidden valley of Mirandilla, there is a stele with this beautiful and inspiring inscription:

“No Castilian land nor country is wilder country than this. There’s poise in the slope, there’s mysticism in the even.”

And speaking about wild, it turns out that in this valley of Mirandilla was shot, no less than forty-six years ago, the movie “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”, a classic spaghetti starring another classic who these days just turned eighty-five; Clint Eastwood was by then pushing forty. Just a kid.

I resumed my journey on a beautiful, cheerful, sunny and cool June morning; despite having to say goodbye to the restaurant where I dined like at home, and to the other virtues of Silos. But long is the road, and many other things along will equally bring me joy.

From Santo Domingo I went to Salas de los Infantes, a town I had already passed through a quarter of a century ago when I was making the Camino de Santiago, one of the finest and most memorable trips of my life; one of those feats that make up your character and leave an indelible mark in the heart and in the mind.

This time, though, the town made little impression on me. Compared to the villages I just passed, mostly Silos, I scarcely found any interest in it. I did a little shopping and kept going along the route through Sierra de la Demanda, on the way to Logroño. That road is priceless: it is one of the most varied and impressive tours that can be done; not only for the often breathtaking landscapes, but above all for their authenticity (vague and hard to express attribute, I know; but easy to understand when you’re there). Because those mountains, those valleys and those villages have got something genuine, original, something that many places have apparently lost. It is a region with character, with a personality that -perhaps- can only be appreciated when compared with other rural areas.

I’d find close to impossible — and unacceptably labourious — trying to elaborate here on all my impressions, so I will just make a few comments on villages and places that called my attention.

Barbadillo de Herreros, noble borough fit in an austere and exemplary Castile landscape, hometown to Francisco Grandmontagne, one of the great forgotten writers of the Generation of ’98, who was offered by Primo de Rivera the Spanish embassy in Argentina. The town remembers him with a memorial plate reading like this: the distinguished writer who managed to bring with dignity, to far off lands, the cadence and beauty of the Spanish language.

Barbadillo, located right in the middle of Sierra de la Demanda, among groves, farmlands and grazing pastures, belongs to what I call “the Spain without complexes”, as evidenced by this old advertising that, despite age, has not been graffitied by the intolerant so-called liberals.

“Downtown”, facing off on both sides of the road, two buildings rival each other in beauty: one, the “Townhall and School” which, in addition to both purposes, also hosts the only bar in town; another one is the old church, of which I outline this curious high relief on top of its side door:

Halfway between Barbadillo and Monterrubio de la Demanda I had the chance to admire one of the purest and most Castilian landscapes I’ve ever seen; one that has all the elements defining the country: brushwoods, green meadows, sheep, groves, the sierra, catching my attention, a snow patch standing the June heat on top of the mountain. Despite my ficklish character, it’d take me years in getting bored of this view.

The news of the abdication of our King Juan Carlos I got me when I was drinking a beer in Canales de la Sierra, another one of the several impeccably traditional villages along this route, thank God missed by tourism; let alone by the building frenzy.

The township of Canales is actually in Logroño, a province which remains deeply Castilian despite their people (and politics) insisting in differentiating it administratively. Canales, holding barely a hundred neighbors (in summer), is nothing less than 1050 m above sea level.

Promenading on the surroundings of Canales places the walker right in the middle of as rural a life as can be found in Spain.

And the must-see visit to the Hermitage of San Marcos, a splendid example of Romanesque, will invite you to meditate for a moment under the shady and fine portico.

But if I had to pick a village taking my breath away in this day’s journey, that was Anguiano; more precisely, Las Cuevas, one of its neighborhoods. It suddenly spouts out, unexpectedly, behind a bend in the road; and it’s located right at the foot of an impressive cliff making a gate to Sierra de la Demanda. Gate in both senses: literally because it is a gorge resembling a doorway or, rather, an entrance through a wall; and in the figurative because, on either side of the ravine, the landscape changes dramatically: just there, the Sierra abruptly ends and the Ebro valley begins; the vegetation also changes, forests reach an end, and weather gets noticeably warmer.

Right at the foot of such cut, hidden and sheltered in a ravine of the Najerilla river, across the spectacular bridge called “Mother of God” (better translated as “Oh my God!”), we find the neighbourhood of Las Cuevas. The Catholic Church had the nerve to build a church at the foot of the very rock, which makes me dizzy just by looking up to the top of the tower. A very impressive view, you can take my word for it.

The bridge leading to Las Cuevas is a true work of art; not so much for its architecture, a single arch, as for its location, as it stands on the rock on both sides of the ravine, no less than one hundred feet above the waters, that go wild and roaring. Unfurtunately I wasn’t able to take a shot properly capturing the scene.

And on the other shore, passing through the aforementioned natural gate, there is Anguiano, the last of the pretty villages on the route from Santo Domingo de Silos (which now seems so long ago).

So, once toured these dramatic landscapes, these colorful villages full of character, who will be impressed by Baños del río Toba, by Najera or Cenicero? Not even Logroño, that charming capital of wine and tapas, could ring my senses that afternoon, except for my stomach, as surely you won’t miss some wines and tapas in Logroño, where you can find them as fine as those in Basque Country, if not better. It is true though that such beautiful city is economically half conquered by the Basques, who consider it theirs. If the inhabitants of Logroño don’t wake up, a fine morning they’ll find their city taken away by those.